LZ Sets a World’s Best in the Hunt for Galactic Dark Matter

ALBANY, N.Y. (Dec. 9, 2025) — The latest results from the groundbreaking LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) experiment have set a new world-leading standard for dark matter detection sensitivity. UAlbany researchers Cecilia Levy and Matthew Szydagis are part of a team of more than 250 scientists who collaborated on the latest findings, presented Monday in a scientific talk at the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF). They will be released on the online repository arXiv. The paper will also be submitted to the journal Physical Review Letters.

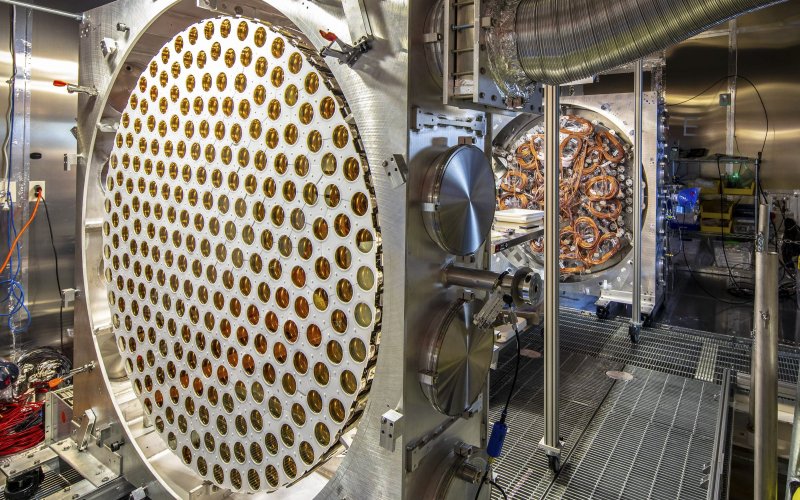

The detector is managed by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and operates nearly one mile below ground at the Sanford Underground Research Facility in South Dakota.

“Dark matter is the invisible scaffolding of the universe and makes up about 25 percent of it: While it shapes galaxies and drives cosmic evolution, we still do not know what it really is and what it is made of,” said Levy, associate professor of physics at UAlbany. “Studying it isn’t just about solving a physics puzzle; it’s about understanding the fundamental structure of reality. Every step we take toward identifying dark matter brings us a bit closer to understanding our universe. We are proud that the UAlbany group has been involved in LZ for over a decade and has made major contributions to all aspects of the experiment, from construction to simulation and data analysis.”

“Numerous UAlbany postdocs, PhD graduate students, master’s students and undergraduate students have all played enormous roles on LZ going back to 2014,” Szydagis added. “They have held leadership roles on calibrations and simulations, both remotely and on site, in South Dakota.”

The newest results from LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ) extend the experiment’s search for low-mass dark matter and set world-leading constraints on one of the prime dark matter candidates: weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs. They also mark the first time LZ has picked up signals from neutrinos from the sun, a milestone in sensitivity, which demonstrates the experiment’s ability to distinguish extremely rare real signals from background noise.

“The agreement between the data on the neutrino signal and simulations based on the NEST software I first created back in 2011 is incredible,” said Szydagis. “The predictive power of our computer simulation has now been proven down to unprecedentedly low energies.”

The new results use the largest dataset ever collected by a dark matter detector and have unmatched sensitivity.

LZ uses 10 metric tonnes of ultrapure, ultracold liquid xenon. If a WIMP hits a xenon nucleus, it deposits energy, causing the xenon to recoil and emit light and electrons that the sensors record. Deep underground, the detector is shielded from cosmic rays, which lets the rare dark matter interactions stand out.

LZ’s extreme sensitivity, designed to hunt dark matter, now also allows it to detect neutrinos — fundamental, nearly massless particles that are notoriously hard to catch — in a new way.

The analysis of the dataset showed a new look at neutrinos from a particular source: the boron-8 solar neutrino produced by fusion in the sun’s core. This data is a window into how neutrinos interact and the nuclear reactions in stars that produce them. But the signal also mimics what researchers expect to see from dark matter. That background noise, sometimes called the “neutrino fog,” could start to compete with dark matter interactions as researchers look for lower-mass particles.

LZ is scheduled to collect more than 1,000 days of live data by 2028, which will make it even more sensitive to possible dark matter signals and neutrinos.

As the collaboration pushes both toward lighter and heavier possible dark matter particles — and even explores unexpected or “exotic” ways dark matter might interact with xenon — the UAlbany team is playing a key role. Their work includes expanding the amount of xenon that can be used in certain analyses, a project driven by graduate students Kian Trengove and Abantika Ghosh. Another effort, led by post-doctoral researcher Gregory Blockinger, who recently earned his PhD from UAlbany, focuses on searching for a potential seasonal pattern in the data that could offer new clues about dark matter.

While LZ has already reached remarkable sensitivity, the search is far from over. More data and deeper analysis will keep pushing the frontier.